Almost every business is technology-enabled in some way these days. Hair salons do their scheduling online, powerline workers train in VR, and pharmacists use AI systems to check for contraindications. There are very few businesses out there that could not be made more efficient and profitable — or provide better services for their customers — through technology.

In most situations, buying software and customizing it makes the best sense. You need a word processor and an accounting system, but it would show boldness to the point of lunacy to build one yourself. Quickbooks and Microsoft Word are worth the few hundred dollars a year. They might not be perfect, but the cost to build and maintain your dream accounting software could run into the millions.

However, in many situations, businesses invent new ways to improve their internal operations or their customer experience. While a comparable off-the-shelf solutions may exist to fit those needs, a custom built product is likely the only way to deliver the required features and processes the company is looking for. Features like these become competitive advantages. Organizations want to own the intellectual property behind their competitive advantages. You don’t want to license these types of systems if your competitors can license them just as easily.

That leaves companies with one choice: Build your own custom software. But the question is whether you should try and build your business-changing application in-house or outsource it to a development agency.

Cost vs. Time

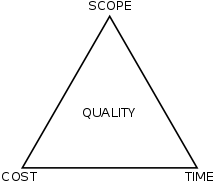

Most decisions in the professional space come down to the project management triangle. If you want to build software of any decent quality, you can pick two of the three corners to move: cost, time, and scope (the number and robustness of features the project has). If you want fast and cheap, you have to shrink the scope. If you want robust and cheap, you’ll have to wait a long time.

The decision to hire an agency or build a team hinges on these three corners. In business applications, scope is usually the non-negotiable — the requirements are the requirements. Building a team takes a lot of time and costs money. Hiring an agency will drastically reduce the ramp up time by comparison, but potentially cost more. If you are worried about quality, remember that you get what you pay for.

Management Structure

Deciding to build out your own development team is not for the faint of heart, but it can have serious benefits.

To build a basic, but healthy and functioning, software team you will need the following:

- A CTO or CIO to handle strategy and management.

- A Director of Engineering to manage the team, build out processes, etc.

- A Software Architect to design the system. (This can be a senior developer for small teams.)

- A couple of DevOps engineers to manage the environments.

- At least one QA expert. (No, developers can’t check the work themselves, I’ve tried.)

- Developers, including full-stack, frontend, and backend developers if you’re building out a product. A good mix of senior, mid-level, and junior developers would be my recommendation to make the team robust.

- A product owner. Preferably someone with management experience

- A scrum master (if you’re following Scrum/Agile).

- UX expert. I cannot understate this role enough! (They can be outsourced if you have to, but are much better to have on the team.)

- A visual designer. Depending on the product you are building, this is the one optional role.

This is the biggest reason to hire an agency. If you want something built well, you really need a team that looks like something similar to this. Depending on your budget and experience, it could take years to put a team like this together.

However, if you have highly technical and experienced upper management there are benefits to in-house teams.

But We Are a Lean Startup

That’s great! Then you don’t need any of the stuff I listed above. But if you are purely a technology startup, then you (I’m guessing you’re a founder), need to be building the tech yourself, or at least have a co-founder building the tech. As the company scales, you can bring on additional help and you will almost certainly start looking like the organize above.

How Long Does It Take To Build a Team?

It depends on if you’re talking about a good team, or just any team. Building an organization from scratch takes time. You need to recruit, hire people, onboard them, manage them, weed out the good, let go of the bad, hire replacements for those let go, etc. You also need to invent, document, and enforce the systems and processes that will lead to the best outcomes. You will need to build a culture of caring, accountability, and quality. So, basically it will take a long, long time. This is a lot easier to do if you have a top rated CTO or a Director of Engineering in place already. Someone who has gone through this process before will be able to get you up and running much more quickly. They will also be able to oversee all stages of the team building from recruiting to delivery.

Recuiting may be the hardest piece of all of this. Good developers don’t want to join companies without histories of good development practices. So if you don’t have someone for new hires to look up to, you’re going to be stuck with coders who are just looking for a job, and they don’t write good code.

In-House vs Outsourced — Conclusion

Unless you are going to go with the lowest bidder, there probably isn’t that much difference between a good internal team and a good agency. Well-run development studios partner closely with their clients and eventually start to act as part of the same company. The developers in agencies like this feel as much ownership in what they are building as full-time employees would — sometimes more.

Price is not going to be dissimilar either. Once you count things like benefits, office space, management scaffolding, training, hardware and software tools, payroll, HR, etc., etc., etc., it’s unlikely that in-house could be done cheaper than even the large agencies.

The real difference comes down to the level of control you want over the team and the type of product you’re building. If you are a small technology startup you would be crazy to hire a big agency unless your product needed to be really good from day one. If you plan on becoming a technology company, you might want try a hybrid of agency and in-house. Finally, if you are a small- to medium-sized company whose existing products or services are not predominantly tech-focused or delivered, I would suggest not doing development in-house.