Solving problems is what my company does for a living. 95% of the time we solve problems by building software. Over the last few years, hardware solutions have entered our solutions tool box more and more. This is largely due to the fact that you can now hook a bluetooth module to some larger device like a printer. You then handle the data processing on some mobile device. Or, we are write software to live on some small-board machine like a Raspberry PI that monitors water temperature or something. These hardware solutions are however, largely integrations, and not actual hardware development.

So when a client asked us to build them a remote control for their interactive TV system, I thought: how hard can it be? This post tries to lay out some of the lessons I have learned while designing, programming, manufacturing, and shipping a custom-built hardware project from soup to nuts.

Like with any new venture, I didn’t know where to start. I know what a remote control is (I use one every day to watch Youtube videos about bad movies) but I’d never really thought about them. Iterative design works in software… so I figured it wouldn’t hurt to just start with something very simple.

Lesson: Just start with something. Anything. Inertia is the enemy.

Humble Beginnings

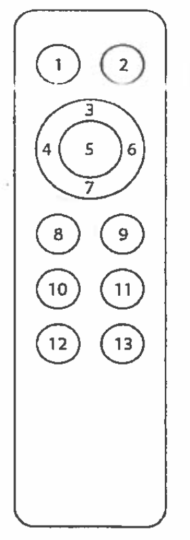

I sketched the thing out on a piece of scrap paper. In my infinite creativity I took a generation one Apple TV remote control (which at the time I thought was very cool) and traced it on some scrap piece of paper. As Picasso said, good artists borrow, great artists steal. I then used dime to trace the d-pad, and a pen lid to outline the function buttons. You never think about regrets when you start something, but documenting your first steps will make you more mindful of the process. I wish I still had that napkin, or receipt, or whatever I first drew it on.

Lesson: Keep baby photos and napkin sketches. Looking back gives your perspective.

Fortunately, I did keep the first digital rendering that I translated into Balsamiq (totally the wrong tool for the job.)

Surprisingly, this very basic initial start was good enough to get some general client feedback and approvals. Now the real work began. We had to actually build a remote control. We had a few connections in the set-top-box manufacturing world and knew engineers and account managers at two of the big TV brands. So we reached out and asked for some recommendations.

Contract Manufacturers

We evaluated a few manufactures in Texas, China, and Taiwan. Most of them were up for the task, but none clicked for us. We were looking for a partner who talked to us about the future, about innovation, and brought their own ideas to the table. We didn’t really know what we were doing, but we knew that we would want to push the limits eventually, and having a manufacturing team who got excited about remote control technology was a must.

Lesson: Find partners who share your values.

The process was slow. This was not our wheelhouse, but it was a fun, tangible project, with a single, definite measure of success – something that is often elusive in software development. So we pushed on. In the end, one of our DRM encoding partners introduced us to a manufacture in Hong Kong. They were responsive, helpful, and had US-based project managers.

Lesson: Ask EVERYONE for help. The more people you speak to the more likely you are to get valuable signal from the noise.

Learn About Everything

Our new vendor gave us a ton of options. Did we know that there are a huge number of molds already out there? Ones that look almost identical to our sketches? And that we could easily customize them? No, no we didn’t. So they went to work sourcing three or four demo units from other manufacturing firms they were familiar with. This way we could send our client actual samples to touch and feel without spending tens of thousands of dollars in manufacturing prototypes.

They also began educating us on IR codes, button mapping, and materials design. While the learning curve was steep, it was rewarding and edifying experience. It is so satisfying to be able to design software systems in concert with hardware. When your code jumps into the tactile world it is just so cool. Working hand-in-hand with the manufacturers, we threw ourselves into their processes, language, legal ramifications, and communication patterns.

Lesson: Learn how to communicate with your partners from their perspective. Even if you are a client, you will benefit from speaking their language.

Test, Test, and Test Again

We tested a bunch of the molds, shipping them around the world for client feedback. We also spent a lot of time hallway testing (asking random people walking by to give us feedback). We gave them to our parents and grandparents, friends and children, and basically anyone who would listen. I actually met one of our client’s customers in an airport (identified by a sticker on her luggage) and dragged the poor woman into user test. I had one of the test remotes in my pocket, and the prototype TV system on my laptop’s local server. We didn’t give her any instructions. She absolutely loved it. The customer felt special getting to play with something before the public do. I learnt more in those 15 minutes with her than anything I had read online about remote design and TV interactions.

Lesson: If you are not showing your product to clients along the line, you are not doing your job well.

We evaluated everything: feel, weight, button squishiness, response time, everything. This was a little easier now that we had a few comparison prototypes, but our clients were very particular group of people. The company’s owner was to give final approval; he oversees much of final the public-facing products. We sent two finalists to him, that we could barely tell the difference between. After he made his selection, I asked for his team to ask him the following day if he could tell the difference, and he made the same choice. They were extremely pleased with the design and functionality – the owner said:

This is so good it makes everything else look embarrassing

Our Client

Which might be the highest compliment anyone has ever paid me.

Lesson: If you want to do something well, take every part of it seriously.

The Trouble Begins

Once we had approved from the client, we gave the go-ahead for manufacturing. Then the Hong Kong problems started. The protests throughout the metro area brought manufacturing to a temporary halt. Workers could not even get to work. Suppliers couldn’t access roads. The whole city came to a halt.

Then the mold vendor disappeared. Our manufacturer had sourced a ready-made mold from another company. One day, our project manager called us in tears because the owner of the vendor’s company had not shown up to work. No one knew where he was. The political situation had made is so that asking questions was not encouraged. Say what you want about the American political system; you don’t have to worry about your business partners not showing up after a rally.

So the search began for a new mold manufacturer. Unfortunately this meant once again going through the approval process with our client. This time it was a little easier because we had learned so much from the first round. After a ton of time and a huge DHL bill, we finally had a new mold, and client approval. Eventually the factories started opening up again, and we were ready to go!

COVID-19

Then the factories shut down. COVID-19 hit China hard, and Hong Kong with it. Almost as soon as we had started printing boards, everything went into quarantine. At the beginning there was some pushback from suppliers, clients, contractors, and even our project managers. But as the scope of the pandemic become obvious, everyone became more tolerant and understanding. It still added almost three months of delays to the project. All while my developers got to move to the comfort of their homes and continue working. More perspective.

Lesson: Like everything in life, it came down to lots of failure followed by perseverance. Feeling frustrated every morning and swearing a lot are the steps in between. With enough failure, swearing, and pig-headedness, stuff works out somehow.

The Final Stretch

The day those first four remote controls arrived in our office felt like we had landed on the moon. We wiped them down with disinfectant wipes and went to work (no one really knew anything about COVID back then!) We did find a small manufacturing defect with the battery connection in two of the remotes, but it was easily remedied.

Then programming began. This went a little smoother due to the fact that my team had done this type of work many times before. We already had IR code programming tables, IoT systems for managing multiple receivers in close proximity and tools too complicated for me to understand that can change the TVs’ or set-top-boxes’ input expectations. It felt… easy, but in reality we had been working on those particular problems for over six years, so the perspective of a thousand small failures didn’t feel anywhere as monumental as the hardware production.

Lesson: Trying new things puts things you already know into perspective.

Where We Are Today

Today, there are tens of thousands of these remote controls out in the wild. People write reviews about them online, and my client mentions them in interviews with international news publications. As a software guy, it continues to be one of those things I’m proud of, and still shocked by the success we achieved from such humble beginnings.

Lessons

- Just start with something. Anything. Inertia is the enemy

- If you are not showing your product to clients along the line, you are not doing your job well

- Keep baby photos and napkin sketches. Looking back gives your perspective

- Learn how to communicate with your partners from their perspective. Even if you are a client, you will benefit from speaking their language

- If you want to do something well, take every part of it seriously

- Like everything in life, it comes down to lots of failure followed by perseverance. Feeling frustrated every morning and swearing a lot are the steps in between. With enough failure, swearing, and pig-headedness, stuff works out somehow. Why do I have to keep relearning this?

- Trying new things puts things you already know into perspective