There has been a lot of hype recently in Tampa Bay about the “Here Comes the Bus” app. This is system that allows parents to see when their kids have gotten on a school bus, and where the bus is. Some parents are concerned that systems like this one could let malicious users, or government agents track their children. So I’m going to give a quick overview of how systems like these work, and why they are not dangerous. We will also look at what parents SHOULD be concerned about.

How it works

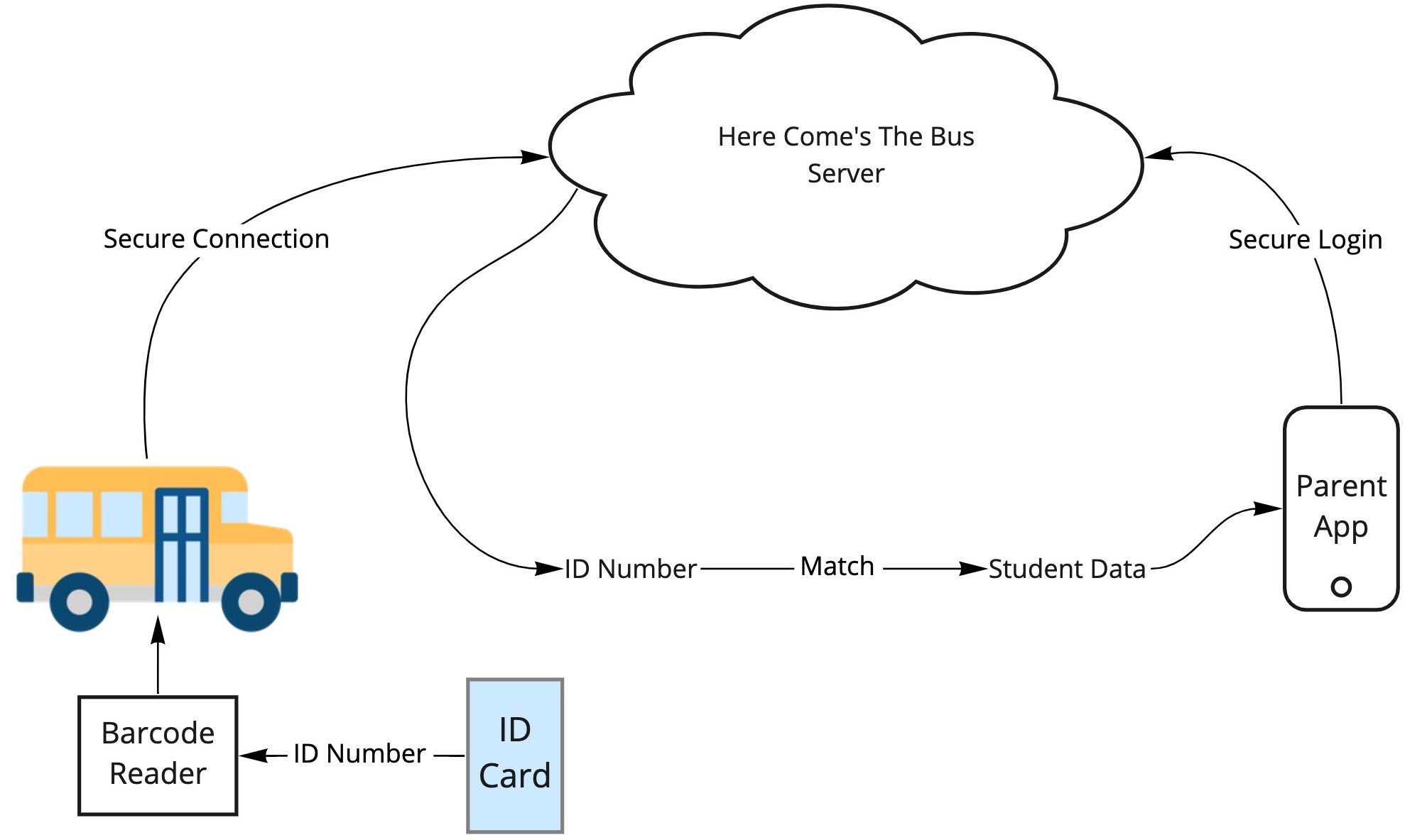

The system is fairly straight forward. Students have either a barcode or a passive RFID chip printed onto their “Bus Pass” – which is just a card they carry around. This card is scanned once the student boards the bus, either with an RFID reader or a barcode scanner (basically the same technology used at grocery stores and clothing shops).

The barcode or the RFID chip carries a simple ID number. This number does not represent the student in any identifiable way – it’s just randomly assigned. The RFID scanner is connected to an internet-enabled device and sends the ID number securely to a server.

Keep in mind, if any data is intercepted up to this point, it is of no use to an attacker. The attacker would at best get a random number that means nothing.

On the other side of the system is the parent’s app. This app is connected to Here Comes The Bus‘ servers, which lets them know that their child is on the bus. The bus also has a GPS tracker on it, which connects to the internet and lets the Here Comes the Bus‘ servers know where the bus is.

That random ID number is then looked up in a database which lets the application know which child has been assigned that ID number. The parent’s device securely requests that information, and it is provided securely down to the app.

It is possible the data coming down to the parent could be intercepted by an attacker. However, as this technology is very secure and is commonly used in almost every piece of software these days (from your health systems to banking apps), it is HIGHLY unlikely.

Could you track kids using their cards?

Some of these bus passes contain a chip, and that sounds scary right? Well, you don’t have to worry too much. These chips are passive RFID chips, the same type of technology that is imprinted in clothing labels to stop theft. Passive means that they need to be picked up by a powered scanner. In order to track a child, you would need to know their ID number (the randomly assigned one), and then set up expensive, high-powered scanners all around town. So it is possible, but there are WAY cheaper and easier ways to track someone. So this seems incredibly unlikely.

Could you track kids if you hacked into the Here Comes the Bus servers?

So the one thing that COULD happen is the Here Comes the Bus’ servers could be hacked. An attacker could break into the database and potentially be able to work out where a child has been, but this does not necessarily mean they will be able to find information on a particular child either. This data is hopefully encrypted, or linked to the school’s secure systems. I can’t speak to how this system has been secured and architected. My best guess is the system was designed with the understanding that this is sensitive data, and great care should be taken over the security. There are also a number of regulations in place that govern the usage and security of student and child data. The Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act of 1998 (COPPA) provides strict regulations regarding a child’s data. The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974 (FERPA) gives parents certain rights with respect to their children’s education records. These two regulations will have been taken into account by the developers and the school board when evaluating this software.

Should I be worried about this?

No system is perfect and inherently has its risks, but these risks need to be balanced against the rewards. I think that the safety aspects of this application far outweigh the highly remote possibility of the system being misused. There are WAY easier ways to track people than trying to exploit a system like this.

So what should I be worried about?

There are real threats and issues out there for you to be worried about. Kids download all sorts of things to their devices, and these downloads represent real, actual threats. Malware embedded in games, social media apps, and even downloaded backgrounds can track your exact GPS location, leak your phone number, show inappropriate content, or steal personal information.

Instead of worrying about the government tracking your kids while you send them to a Public school, take a look at your kids’ actual devices. Install something like Norton Security Online and Norton Security for iOS or Android, or Malwarebytes. Also talk to your kids about what apps they’re using, and listen to hear for anything strange about their data usage, or content that is coming up unexpectedly, or unusual phone calls they’re getting. These are indicators of real threats to kids’ information and of valid concern by parents.